Alper Görmüş

The Turkish original of this article was published as Söz mühendisliğiyle muhalefet: Taze örnek on 4th January 2016.

Tarhan Erdem, a former general secretary of the CHP, wrote in the daily Radikal some years ago about the CHP’s style and practice of opposition. Every morning all newspapers would be screened at party headquarters, he said; statements by spokespersons of the ruling party would be carefully noted, those considered polemically vulnerable would be selected, and memorable responses would be coined in rhyming words.

It is in the nature of things that when you restrict your opposition to such a limited area, every now and then you are likely to find yourself with no materials. Put in another way, if you cannot find sufficient statements to build your opposition on, you either resort to demagogical retorts sprinkled with bad jokes, or you try to produce your own materials by distorting some statements in order to make them more opposable.

Eventually the CHP came to realize that with this notion of opposition it could not possibly become a real alternative for ruling the country, and over the last few years began to try to concentrate its energy less on such polemics and witticisms than on what it intended to do if and when it came to power.

However, this whole style of opposition, focusing less on forcing the ruling party back step by step in order to present itself as an alternative, and much more on obtaining the upper hand in spiteful exchanges of a moment, is now on the way to taking over as the style and approach of all opposition, whether from the left or the right. Such an opposition based only on word-slinging and witticisms might have been criticized as no more than innocently “ineffective” – provided it hadn’t resorted to other and dirtier means. But as I have already said, it does not stop there. Selected statements, expressions, individual phrases or even words are picked out of context, distorted, restructured, and demagogical polemics are then launched against these newly derived sentences. Hence from here on, this type of opposition begins to be saddled with ethical problems.

Why ineffective?

What is interesting is that, as the ruling party that is the target of such oppositional arrows or barbs is perceived as a hate object by some sizable sections of society, these ethical issues should not at all bother those groups or sections. For them, the only thing that matters is the momentary chill provided by that spiteful “victory.” They seem to think that certain ethical transgressions can be tolerated to that end.

But the problem is, that their pretense at not having noticed these verbal engineering efforts does not mean that the other half of the society does not notice them either. Thus, yes, this sort of opposition does keep sustaining the hatred of a section of society, but it also helps consolidate the other half’s adherence to the ruling party. This half therefore begins to turn a deaf ear to any fair or genuine oppositional critiques of the government, so that in the end, the opposition serves only to preach to the converted — to sooth the feelings of those who are already in the opposition.

Another aspect of this sort of opposition is that the words it highlights to attack (of course in their “doctored” hence “useful” forms) are rapidly transmitted to the “West,” so that the West also comes to be included in the campaign. When this second wave is carried back to Turkey from the West, it once more strengthens the consolidation of the rest of society around the ruling party.

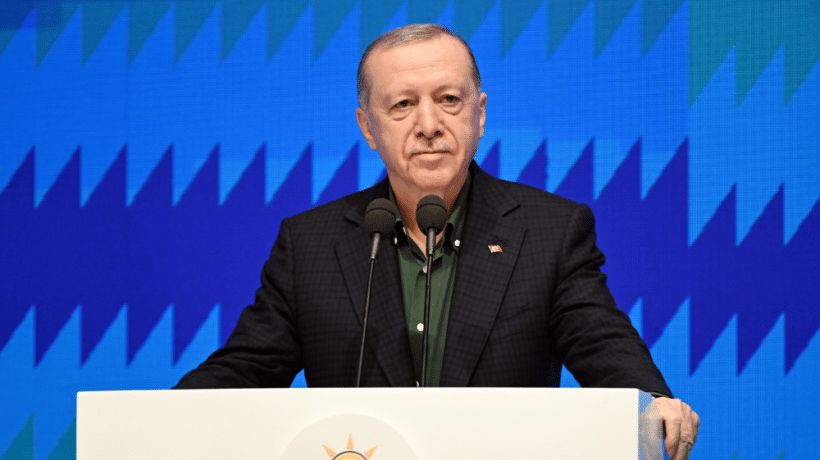

Returning from his visit to Saudi Arabia, President Erdoğan was interviewed on the presidential system, during which he mentioned Hitler’s Germany as an example of the system’s applicability to unitary régimes. This called forth a wave of opposition that exemplifies everything I have said above. all these properties. Let us first recall the particulars of the case, and then discuss it together.

How to cut off a speech at the “right” point

A journalist reminds Erdoğan that on a recent television program, Prime Minister Davutoğlu had said that a presidential system could also be applied in unitary states. Then he asks whether he, the president, agrees with this. President Erdoğan replied, word for word, as follows:

“That’s right, you cannot say that there is no such thing as a presidential system in unitary states. There are some examples in the present world. Actually there have been examples extending from the past to the present. You can see this in Hitler’s Germany, too, and later in various other countries as well. What matters is that the presidential system in question should not have a structure, a character that bothers the people in practice. That is, if you are dispensing justice, which is what the people seek and expect; if it is there, there should be no problem. And now, too, we cannot possibly say that all presidential systems are perfect from A to Z. Aren’t there places where there is a presidential system and there are no problems, yes, such places also exist.”

The talk goes on, but I will cut it off here, because this is the part that has become the subject of debate.

I am cutting it off here, but others have cut it off before this point. In news reports with headlines of the “Erdoğan cited Hitler’s Germany as presidential system example” or “Erdoğan: There was a unitary presidential system in Hitler’s Germany” sort quoted only the following part from Erdoğan’s words:

“That’s right, you cannot say that there is no such thing as a presidential system in unitary states. There are some examples in the present world. Actually there have been examples extending from the past to the present. You can see this in Hitler’s Germany.”

The statement from the President’s office

When I saw this much, and only this much, everywhere I looked, I didn’t find the statement published in the President’s official website convincing at all. That statement argues that “the ‘Hitler’s Germany’ analogy was blatantly distorted by certain media sources in such a way as to impart the very opposite meaning.” It further notes that Erdoğan had actually underlined three points:

“1) There can also be presidential systems in unitary states. Presidential systems don’t have to be based on federalism. 2) In both parliamentary and presidential systems, the main thing is adhering to the principle of justice in order to meet people’s expectations. 3) In both parliamentary and presidential systems, if the system is abused, bad governments may arise and lead to catastrophe, as was the case with Hitler’s Germany. Neither the parliamentary system nor the presidential system may not be able to prevent such developments by itself. The important thing is the adoption of a just mode of government which serves the nation.”

The statement ultimately explains why Erdoğan could not have cited a presidential system like Hitler’s Germany as a positive example:

“Such an analogy is out of the question. Our President has declared the Holocaust and anti-Semitism, along with Islamophobia, as equally crimes against humanity. It is unacceptable to try to interprete his statement as an affirmative reference to Hitler’s Germany.”

As I’ve already said, since everywhere I looked I had seen only the “short version” I have quoted above, initially I did not find this statement at all convincing. But when I then sought and found, and listened to the original and complete statement from Erdoğan’s own recorded voice, I came to realize that Erdoğan had truly spoken along the lines later explained on his website, but because it had been cut off at a convenient point and manipulated to make it usable, it had been made open to the assertion that Erdoğan had cited Hitler’s Germany as a positive example for the presidential system. (To this I have to add that speaking without a text, Erdoğan had, as he sometimes does, not really clarified what he meant, thereby leaving the door ajar for those with ulterior motives.)

The second act: the Western media

This, indeed, is exactly what happened as these words were repeatedly used and consumed to the outmost within Turkey. Then came the second act: Erdoğan’s words were transmitted to the Western world in the short version I have quoted above. The anti-Erdoğan Western press jumped on this opportunity, so that Western media of both the right and the left reported the incident with the following headlines:

The Times: “Erdoğan wants to be Turkey’s Hitler…”

Time: “Turkey’s President Wants To Be More Like Adolf Hitler.”

The Daily Telegraph: “Turkey’s president says all he wants is same powers as Hitler.”

The Independent: “Turkey’s President Erdoğan cites ‘Hitler’s Germany’ as example of effective government.”

Further on, these stories began to be cited in the Turkish media, thus completing the cycle. But the juiciest item was a piece of front-page news carried by Cumhuriyet three days after the “event.” This entailed a summary of what an American political science professor by the name of John A. Tures had blogged at the Huffington Post. According to Cumhuriyet, Tures had asserted that Erdoğan’s words were not a gaffe, adding: “For the authoritarian Erdoğan, this is a rare moment of truth reflecting a dictator’s feelings.”

When I read this comment, I thought that Professor Tures was trying to say that Erdoğan’s tongue had revealed what his brain was trying to hide; that, in other words, this was a lapsus. But no, apparently the professor is talking about the conscious and not the subconscious, saying that Erdoğan “honestly” desires Hitler-style power.

This is what amazes me most regarding this sort of opposition: The likes of Professor Tures make these grandiose comments on the basis of the “processed” materials that they are served; hence they can be excused to a certain extent. But how can those who have had access to all the material, that is to say those who know the truth, can go for such engineering just to be able to elicit acute reactions in the short run? And how can they not see that through such engineering, they are preventing the birth of a genuine and effective opposition?

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.