The story of how Mustafa Kemal tolerated, and then quashed the Green Army (Yeşil Ordu) is well-known, as is the way he set up and then destroyed an official Turkish Communist Party. More obscure is the manner in which some of Mustafa Kemal’s political statements on cooperating with the Bolsheviks would later provide all Turkish leftists with material to shore up their political legitimacy. In sum, Turkish leftists could always resort to carefully chosen and interpreted statements or events from 1920-1921 to prop up their political legitimacy. This also enabled Turkish leftists to operate as quasi-Kemalists/Atatürkists, even nationalists, at the exact same time that they were staunch Marxist-Leninists (1). And despite that alliance with or tinge or hue of “bourgeois-nationalism,” Turkish Marxists were supposedly waiting and working for the proletarian revolution, in the manner that Lenin, then Stalin, had told them to (2).

One can understand why that ideological outlook might have been compelling during the Cold War, at least before 1968. The 1960 military coup, which targeted Turkey’s first democratically-elected political party, was carried out by the younger ranks of contemporary military officers. Most possessed a nationalist-statist Third World type of ideology, heavily borrowing from Leninist anti-imperialism and accelerated national developmentalism. By the same token they were also very dubious about parliamentary democracy, which they saw as the hotbed of popular, hence reactionary, hence counter-revolutionary (meaning anti-Ataturkist) ideas. The 1961 constitution that they forged opened up Turkey’s political system to leftist ideas and parties, and through the so-called “national remaindering system” the Turkish Workers’ Party (TİP) was actually able to win 14 seats in parliament (with less than 3 percent of the popular vote) in the 1965 election.

But the Turkish left’s Marxism-Leninism, stretching even further into Castroism or Maoism, drove it steadily toward extremism, fragmentation, and violence (3). Violence and interpersonal rivalries created a series of minor Che-like martyrs, and morbid concentration on ideological purity led to extreme factionalisation in the form of more than fifty distinct groups. But because the Turkish left was actually limited to a small sector of Turkish society, and was not a dominant political force, it was never obliged to deal with larger political realities. Similarly, the military coups in 1971 and 1980, and the resulting jailings, torture, and deaths, did not inspire profound self-examination among most Turkish leftists. Instead, a cult of victimhood, even more intense focus on martyrs, and radically defiant, self-righteous and maximalist political stances continued to prevail. Atatürkist/Kemalist rationalizations based on Mustafa Kemal’s statements from the early 1920s protected Turkish leftists from the necessity of questioning their nationalism, and even pushed them to flaunt their Marxist-nationalist credentials. But Turkish society in general did not welcome leftist ideology, so the left’s activists generally went into academia, the press, underground militant groups, or exile (4) especially following the 1971 and 1980 coups. Violent extremist organizations such as the PKK and the DHKP-C are actually remnants of Turkey’s splintered 1970s leftist environment (5).

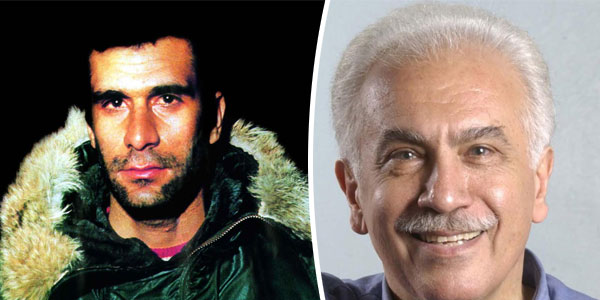

The USSR’s collapse and China’s gradual transition to a market economy should have disabused Turkish leftists of their revolutionary fantasies. But that, for the most part, never happened. Marxist-Leninist Turkish leftists still have not gone through the process that the German left went through in the late 19th century, abandoning radical, violent political methods for peaceful, democratic struggle within a democratizing society. Instead, Turkey’s left, or what is left of it, still fetishizes its martyrs, such as Deniz Gezmiş or Mahir Çayan (6), but meanwhile also features unscrupulous political opportunists like Doğu Perinçek, who has switched from Maoist revolutionism to left-nationalism and neo-Ataturkism, using his state and military ties to remain politically active for the past 30 years.

Socio-political isolation and steadfast denial of the changing scene of world politics have enabled Turkish leftists to remain convinced that the proletarian revolution is still on its way — even as many have obtained university educations, have become well-to-do professionals, and have sometimes gained even greater wealth. After all, not all of the leftist militant groups present in Turkey get their financial backing from elements in the military or the state bureaucracy — many benefit from wealthy individuals’ largess.

Lenin’s theories continue to provide ideological legitimacy for such behavior. As long as a person convinces himself or herself that this is all in the good cause of aiding the bourgeois-nationalist revolution on the way to the future proletarian revolution, a six-figure salary, a Porsche 911, an apartment or villa in Kemerburgaz/Göktürk, or a summer home in Bodrum won’t cause excessive pangs of conscience. Even if such funds are channeled to an armed and violent militant group, it’s all good if they’re working for the proletarian revolution, or can at least be interpreted as such. All this sounds preposterous, but it is the daily reality of the Turkish left. And it has cost countless lives.

This is why the Gezi Park protests, despite the nearly total absence of working-class involvement in the movement, were interpreted by the Turkish left as the harbinger of the expected revolution. Or, more accurately, the Turkish left allowed itself to be easily conned into believing that. This is why certain Turkish media publications covered the protests with jargon suggesting revolution, and books with titles like “The Revolution Winked [at us] in Taksim” (Devrim Taksim’de Göz Kırptı) or “The Gezi Resistance” (Gezi Direnişi) appeared in the protests’ aftermath. Even some of Turkey’s most respected professional intellectuals, who should have known better, jumped on the Gezi revolutionary bandwagon, and exposed how deeply their ideological instincts were rooted.

(to be continued)

NOTES

(1) See: Cemil Koçak, “Kemalist Nationalism’s Murky Waters,” in Turkey between Nationalism and Globalization (ed. Riva Kastoryano), pp. 63-70.

(2) This is one of the many Turkish social phenomena that Orhan Pamuk discusses in the chapter in his novel The Black Book titled “Hepimiz O’nu Bekliyoruz” – in Turkish, the third person singular pronoun “o” has no gender, so the title of the chapter could be translated as “We are all waiting for X.” Pamuk’s The New Life, which followed The Black Book, dwells on similar themes. The New Life begins with the famous sentence, “Bir gün bir kitap okudum ve bütün hayatım değişti” (“One day I read a book and my whole life changed”).

(3) For a unique and important reflection on that period, see: Halil Berktay, “Unutulan darbe: 12 Mart; unutulan tarih: 1965-1971” (A forgotten coup: 12 March; a forgotten history: 1965-1971), https://serbestiyet.com/yazarlar/halil-berktay/unutulan-darbe-12-mart-unutulan-tarih-1965-71-771080.

(4) The associated diaspora in Europe then became the international support and finance network for such organizations. Especially Germany and Belgium have been havens for the PKK and DHKP-C since the 1980s.

(5) Comparable is the Greek violent extremist organization known as 17 November, which was finally broken up by the Greek authorities in 2002.

(6) The pantheon of martyrs is updated according to political junctures. The Gezi Park protests added several figures who have been treated in a nearly Christ-like manner.

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.