About six months ago, the NYT brought in (head-hunted?) award-winning journalist Patrick Kingsley for their Turkish coverage. The reasons were immediately clear. Kingsley is a better writer than Ceylan Yeğinsu et al., and turns out copy at a greater pace.

Of course, while sticking to the existing, Turkophobic editorial line. For beyond his writing skills, Kingsley has merely continued the NYT’s constant stream of invective aimed at Turkey’s political leadership. Now the invective is just more richly creative, and there happens to be more of it.

Overall, that means there’s not much reason to pay any attention to Kingley’s articles. Still, his piece on the first anniversary of Turkey’s 15th July 2016 failed putsch can be used to exemplify the unchanging nature of the hatred aimed at Turkey by the NYT and its editors.

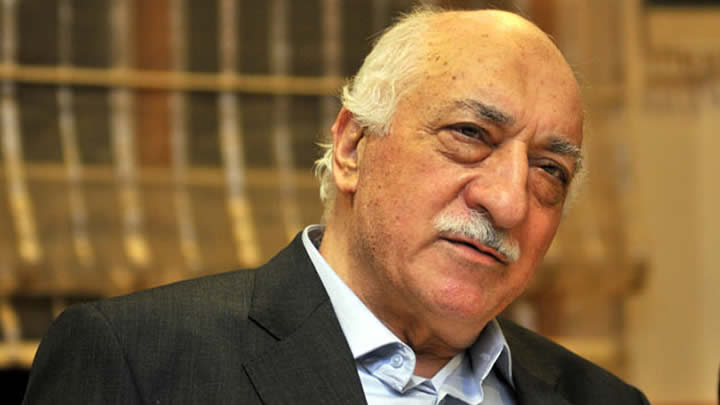

Kingsley’s article, published 13 July 2017 and titled Mysteries, and a Crackdown, Persist a Year After a Failed Coup in Turkey (1) is intended to question the Turkish government’s narrative on Fethullah Gülen’s failed putsch. The article is wholly based on insinuation, with the sole aim of manipulating the reader’s perceptions without any hard evidence.

In order to create a sinister air, Kingley provides a list of “mysteries” connected to the Gülenist coup. As always with the NYT’s reporting on Turkey, the problem is that the mysteries claimed by Kingsley are nothing of the sort, and serve only to illustrate the reporter’s lack of language skills and consequent, excessive dependence on his native-speaker informants.

Let’s start with Kingley’s first “enigma,” which he labels “Who Was Involved?” After beginning the article with the usual attacks on Turkish President Erdoğan (2), which are designed to prejudice the reader’s approach to the rest of the article, Kingsley suggests that there is still some doubt about who exactly carried out the coup. Kingsley neglects two essential points.

First, essentially no one in Turkish society doubts that Fethullah Gülen was the coup’s instigator and that his adherents carried out the plot, no matter what any particular person’s political allegiance might be. In other words, Turkish society doesn’t feel the same confusion that Kingsley claims is present. So Kingsley is telling international readers that a question exists, when it doesn’t actually exist.

Second, Kingley also refers to details in the court proceedings to claim that a lack of clarity exists about the coup’s actors. In reality, there is now a mountain of data – the vast majority in Turkish and thus apparently inaccessible to Mr. Kingsley – that has accumulated through the investigations, suspect confessions, and courtroom testimonies. That data shows without a doubt that Gülen and his organization were the instigators.

Nevertheless, Kingsley proceeds to utilize those details to assert that it is unclear whether disaffected Kemalists in the military may have played a role. Actually, this is not an issue at all, and few in Turkish society give much attention to this idea. The accusation that Kemalist officers were involved has been bandied about in the Turkish press since last July, but with no lasting effect. On an individual basis, some militant Kemalist officers may have been so blinded by their hate for Tayyip Erdoğan so as to choose to throw in their lot with Fethullah Gülen, whom they also despised just as intensely — until December 2013. But they would be a only a tiny minority of the plotters at the most. The vast majority of the plotters were and are clearly Gülenists. Finally, most who have examined this problem closely have concluded that collaborationist Kemalist officers were not a significant element in the putsch (3). Neither has any other evidence emerged that would suggest that Kemalist officers played a serious role in the putsch.

Kingsley’s second mystery is labeled “Who Knew What, and When?” Here he claims that details of exactly how certain prominent state officials became aware of the coup plot are unclear, and then uses this to segue into Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s (head of the prime opposition Republican People’s Party, CHP) claims that the event was a “controlled coup.”

This issue, unfortunately, is one of the most regrettable red herrings that has emerged from the event. Generally, those who have latched onto the “controlled coup” narrative are grasping at straws in order to assuage their political frustrations. We know in detail, step-by-step, what happened that day, but those details are not being reported in the international press (4).

The reality is that the testimonies provided by important figures to the parliamentary investigation committee, as well as the tens of thousands of pages of indictments, the admissions obtained through plea bargains, and the courtroom statements from the many accused of collaborating in the event, have made all the details of how the coup was planned and how it unfolded extremely clear. TRT World recently released a 130-page English-language report that summarizes those details (5), but it should be stressed that the information in that report has been available in the Turkish press all along for those who took the time (or had the ability) to look and read.

But the accusation of “controlled coup” deserves special attention. If one is to believe that government officials allowed the coup to unfold in order to obtain political advantage, that person must maintain the belief that President Erdoğan would send some of his closest acquaintances to their deaths. One of the democracy martyrs shot by soldiers outside a Greater Istanbul Municipality building in the Saraçhane neighborhood was Professor İlhan Varank, the older brother of Mustafa Varank, one of President Erdoğan’s official advisors (6). In think that anyone who claims that the coup attempt was “controlled” needs to carefully examine their own conscience.

(to be continued)

NOTES

(1) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/13/world/europe/turkey-erdogan-failed-coup-mystery.html?_r=1

(2) Kingsley writes, “Far from ending the rule of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it tightened his grip on the country, giving him the political room to impose a state of emergency that is still in effect; fire or suspend about 150,000 dissidents and accused coup plotters; and arrest roughly 50,000 people.” Kingsley chooses not to mention that Erdoğan is Turkey’s democratically-elected President, and that the actions mentioned are both far less draconian that what was experienced in, for example 1980, after that year’s military coup, and to be expected after a broad, secretly organized cult uses mass violence in an attempt to take over state institutions.

(4) Nor in the Turkish opposition English-language press, such as Hürriyet Daily News, which is generally followed by the foreign observers, journalists, etc. who do not know Turkish. More on this issue in the next installment.

(5) http://www.trtworld.com/sites/default/files/trtworld_research_centre_history_and_memory.pdf

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.