… it may be difficult for intelligent and well-intentioned academics and consultants even to grasp what is happening in environments so different from their own, and shaped by such different histories and cultures. (1)

The last three months since Trump’s Electoral College-facilitated election have been gut-wrenching. And then he was inaugurated… All of this, for those of us in Turkey, came on top of the trauma from the failed mid-July coup in Turkey, which took nearly 250 lives. The past seven months, after an already draining previous three years, have been extremely trying.

So, for the record, and because this has been churning around in my mind all the time that I have been observing the Trump commentary in Turkey and the U.S., I want to state something that is vital for historical clarity in the coming years:

The comparisons between Trump and Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan, from both the pro- and anti-Erdoğan commentators on both sides of the Atlantic, are faulty on all levels, ranging from the superficial to the fundamental.

In a case of political convenience for everyone involved, American pundits are mistakenly equating U.S. political stances and disputes with those in Turkey, and Turkish commentators are confusing Turkish socio-political realities with those in the U.S. Copious face-palm material has flown unabated from both sides since November 8, 2016.

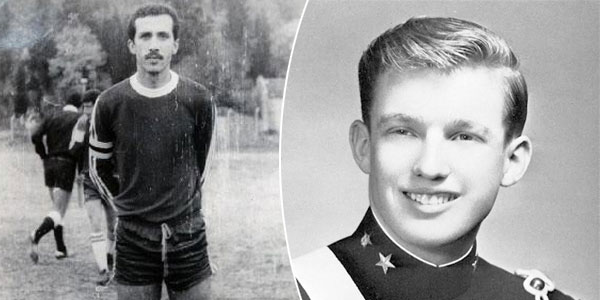

Let’s start with the basic personal facts. Donald Trump was born into great wealth while Erdoğan grew up in a rough working-class neighborhood in central Istanbul. Trump went to an elite private military high school while Erdoğan drove a public bus at a time when Istanbul’s infrastructure was truly at the level of the “Third World.” Trump’s actual interaction with and knowledge of the masses appears to be nil, while Erdoğan emerged from those masses. Trump’s supposedly populist electioneering consisted of blustery slogans backed up by smoke, mirrors, media manipulation, and Vladimir Putin (2), whereas Erdoğan, as everyone readily admits, is able not just to “talk the talk” but also “walk the walk” of a populist politician. The difference in personal background between the two men could not be more pronounced.

How about their political careers? The routes which the two took to electoral victory are different in the same way that a stroll in Central Park and trekking the Lycian Trail (3) are different. Trump’s first publicly-elected position is that of U.S. President — he has no other political experience, and he actually lost the popular ballot by nearly three million votes. Instead, Trump’s inherited riches made him a public figure in the 1980s, and in the following years his relentless self-promotion on TV and other platforms kept him in the public’s attention. Massive wealth, plus decades of public image aggrandizement and that ancient Electoral College quirk in the U.S. voting system added up to the presidency for “The Donald.”

Tayyip Erdoğan got his start on the bottom rung of Istanbul’s no-holds-barred political ladder, and worked his way up to municipal, then city-wide prominence that resulted in his election as mayor for the greater metropolitan area in 1994. After being jailed by the Turkish military (via the “independent” Turkish judiciary) for reading a poem at a political rally, in mid-2001 Erdoğan was proclaimed leader of the new center-right party that emerged from the latest closure in a string of Islamically-oriented political parties banned by the Turkish state. Superior organization, better understanding of the Turkish people’s political desires, and the political opposition’s disgrace gave Erdoğan’s party, the AKP, a large victory in the November 2002 general elections. Erdoğan and/or the AKP have won every election since by double-digit percentage points. Again, no similarity whatsoever between Trump and Erdoğan’s political histories is discernible.

The most difficult topics, judging from the inability of pundits across the range of Turkish-U.S. perspectives to understand them, are the stark historical, political, and social differences between the two nations. The United States has been a stable democracy for more than 200 years. It achieved industrialization in the last half of the 19th century, and for the past century has been the world’s biggest and most productive economy. The socio-economic phenomena experienced by the U.S. since WWII have usually anticipated the trajectory of the world’s other industrialized societies. The U.S.’s two dominant political parties have appealed to the same constituencies since WWII: the Republicans get their votes from the wealthy upper-classes, as well as from middle- and lower-class whites that share the vaguely-defined values of the rural U.S. The Democrats, on the other hand, obtain the vast majority of their votes from the middle- and lower-classes en masse. Starting with Bill Clinton’s centrist economic policies, the Democrats have been also able to appeal to a minor section of the U.S. wealthy, but the narrative claiming that the Democrats are “liberal elites” is nothing more than a talking point developed by the U.S.’s conservative media over the past twenty years.

Turkish politics is historically and socio-economically entirely different from U.S. politics. Turkey is an industrializing society which shares many socio-political problems with other comparable societies. Starting in the mid-19th century, state bureaucratic elites, backed up by the emerging officer and intelligentsia classes, began a top-down project to mold Late Ottoman, then Modern Turkish society to their radical modernizing vision. Turkish electoral politics, which started haltingly in 1876 with a constitutional monarchy, a powerless parliament, and non-transparent voting, did not become really democratic until 1950. And even then, every time popularly-elected political parties threatened the elite control of state institutions, the military stepped in to reverse the situation. This meant that Turkish state institutions, including the judiciary, never became modern, professional, democratically-accountable institutions. This did not begin to change until the 21st century, i.e. only about ten years ago.

One outcome is that the political party representing that original state elite and the ideas associated with them, that is to say the CHP, maintains a solid voting bloc of 20-25 percent, but nothing more than that. This translates into the upper- and upper-middle-classes in Turkish society, plus sections of some other smaller groups, such as Alevis, who feel that they lack an alternative and see the CHP as their only political option. The CHP’s ideology is also a smattering of concepts preferred by their social base that have their ultimate sources in a variety of imported European intellectual traditions, ranging from nationalism to positivism and even Marxism.

The AKP, on the other hand, find their support from the middle- and lower-classes, the sectors that were frozen out of politics by the bureaucratic and military elites that once led Turkey’s industrialization and modernization process. Those voters see the AKP as, if not perfect, the only alternative to the CHP “secular elites” who despise their (the AKP voters’) stubborn attachment to traditional cultural values, however they might be defined. In sum, there is nothing in common between the political history of the U.S. and Turkey, their social realities, or the voting base of Trump and Erdoğan’s respective parties.

(to be continued)

NOTES

(1) Eric Hobsbawm, The New Century (Abacus, 2000), p. 166.

(2) https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/23/opinion/populism-real-and-phony.html; https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/01/29/the-macroeconomics-of-reality-tv-populism/

(3) For information about the Lycian Trail: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycian_Way

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.