[18th May 2021] Surely not coincidentally, it all started on Temple Mount with a crass intervention against Muslim worshippers in the Mescid-i Aksa — on the eve of Jerusalem Day.

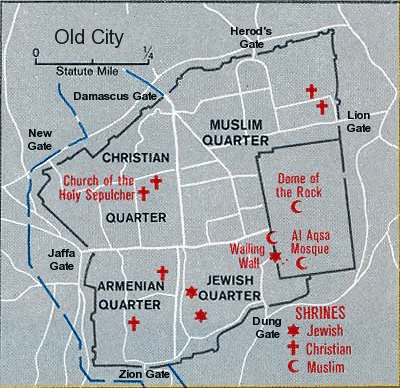

During the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel seized not only the Sinai, the Golan Heights, and the entire West Bank, but also the Old City section of Jerusalem that since 1948 had been in Jordanian hands. Ever since, 7th May has been an official Israeli holiday. One of the various celebrations marking Yom Yerushalayim or Jerusalem Day is a flag-waving parade of conservative Jewish youth that is known as Rikud Hadegalim or “the Dance of the Flags.” Starting in Jerusalem’s new and modern districts, it enters the Old City through the Damascus Gate, winds its ostentatious, indeed provocative way through the Muslim Quarter, and concludes with mass prayers in front of the West Wall or the Wailing Wall.

They are, in other words, ritually reconquering the city again and again. The picture above was taken during the 50th anniversary celebrations in 2017. The crowd is massing on Jaffa Road prior to storming through the gates. It is a bit reminiscent of the 29th May 1453 commemorations in Turkey. But the big difference is that the Israeli right is scratching open a rather recent wound, barely half a century old, and doing it rather deliberately to spite the current, living, and quite sizable Arab population of Jerusalem. Hence the parade is controversial even within Israeli civil society and in the eyes of the country’s oppositional democrats. Thus in May 2015, the Israeli High Court of Justice was petitioned to prevent the parade from marching through the Muslim Quarter. It was rejected, but the justices banned the use of slogans like “Death to the Arabs!” and charged the police with promptly arresting those that did so. Just this verdict by itself hints at what the atmosphere might be like.

Still, it is different to witness it at first hand, up close and personal. It happened to me fifteen years ago. I fell right smack in the middle of a Jerusalem Day parade. Once is more than enough. I don’t quite know how to describe the experience.

It was Spring 2006, the second semester of the 2005-2006 academic year, when I was full-time at Sabancı University, but thanks to the enthusiastic approval and support of the late Tosun Terzioğlu, was also teaching part-time, three days a week (though on a voluntary basis) at Greece’s Panteion University. They did cover my accomodation and air fare, so I would fly to Athens Wednesday morning, lecture for three hours that evening, keep office hours through Thursday, lecture for another three hours Friday evening, and fly back to Istanbul early on Saturday. Then on top of this there came another invitation from my historian friends in Israel, inviting me to share with them, too, my thoughts on Turkish nationalist historians of the Ottoman Empire in the form of two lectures, one at Tel Aviv University (TAU) and the other in the Negev desert, at Beersheba’s Ben-Gurion University.

So I went, of course, and first spoke at TAU, where, on the way to addressing questions of historiography, I dwelt on how modernist Turkish nationalism’s Unionist and Kemalist generations’ mission to impose civilization from the top down on (what they saw as) a backward and primitive society had, along with some real gains for the new nation-state, also generated (or deepened) a serious socio-cultural split by creating (or expanding) an alla franca sector within the overall matrix of an alla turca society. I tried to explain how the residents of this alla franca enclave felt themselves besieged and threatened by the rest. I did say a lot between the lines, I must admit. I touched upon what is known as “the Masada complex” in Israeli history (and politics). After the Great Revolt of AD 66, as the First Jewish-Roman War was drawing to a close, rather than surrender to the Roman legions 960 rebels who had taken refuge on the rocky Masada plateau are said to have committed suicide by jumping into the abyss. Recorded by the historian Josephus, it has turned into a metaphor for Israelis’ self-perception as being under constant siege by the Arabs but determined to resist to the end. So when I let drop something about “the Kemalists’ Masada complex,” most everybody understood what I was implying about “the West’s two advanced outposts in gthe Middle East.” But I also went further by directly suggesting comparions between official-lining Turkish historians’ neglect of Turkish nationalism’s victimized ethno-religious “others” (such as the Armenians), and how the Nakba is neglected by official-lining historians in Israel.

Some of my audience probably appreciated my double critique while others were clearly quite hostile to it. Soon Martin Kramer came up to me. At the time he was the director of the Moshe Dayan Center. What was (and is) this MDC? A think-tank initially proposed by Mossad head Reuven Shiloah, and on that basis founded in 1959, to serve openly, officially, explicitly as a bridge between Israeli intelligence and the academic world. That’s what they say on their own web site. This was what Kramer was running, and that is more than enough for me to leave the rest to your imagination. We had met earlier in Toledo, at an elite forum (held under Chatham House rules) on “Europe and Islam in the 21st Century.” It hadn’t been a pleasant encounter. During a coffee break the late Elizabeth Zachariadou had made a few light-hearted quips about Bernard Lewis, which had infuriated Martin Kramer. I’ll never forget how, this time in Tel Aviv, he very coldly said something like “Now I understand what you are doing.” It sounded like: now I have identified you, decoded you, exposed you, seen you for what you are. Years later, in the midst of all the post-9/11 Islamophobia that was washing over the US, I read how Kramer had become one of the two founders of the Middle East Forum, one of the most militant and rigidly rightist loci of intellectuel terror targeting academic freedom at American universities.

After some further small talk, it was over and we left. That evening, I had dinner in Jaffa’s harbor district with my host Amy Singer and Prof. Michael Winter, who sadly passed away last year. My next day was free. I took a minibus to Jerusalem. I had been warned that I shouldn’t stay too late since it was going to be 7th May, hence Jerusalem Day, and that there would be this march in the afternoon, which I would do well not to get involved in. Readers who are not familiar with Jerusalem can refer to the map of the Old City at the very top. So I did what most tourists do by first going into the Christian Quarter and visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I then walked along a section of the Via Dolorosa to get at the suk, the covered bazaar. As in the above file photo, in mid-morning it was still a lively dash of color. I went into a few shops to buy lots of posters, which I rolled up and put into a long cylindrical container. From the New Gate, I took the stairs up to the top of the circumvallation ordered by Suleiman I (1520-1566). I walked all along the walls, looking down at the crowded worlds of the Christian, Armenian, Jewish and Muslim Quarters below me. Just as I was coming back full circle, I felt tired and sat down to rest. After a while I got up and made it back down by the New Gate. It was already noon. I thought that I should be heading back as soon as possible.

And then I noticed that I didn’t have my carton container with me. I realized that I must have left it where I stopped to rest. I checked my watch; I realized that I was running out of time. But I couldn’t possibly contemplate leaving behind all those lovely posters of the Dome of the Rock, the Mescid-i Aksa, the Doors of Jerusalem, or Mount Olive (for which I had also paid a lot). Even though I knew that I was taking a big risk, I ran back up the Damascus Gate, and ran as fast as I could along that uneven wall-walk to where I had taken a break. Then I came to a sudden stop and did not quite know what to do. Three or four IDF (Israeli Defence Force) men were sitting in the same spot. They had set up a machine gun nest, with the barrel pointing down at the Muslim Quarter. They were very young, maybe only twenty. They caught on and started laughing as soon as they saw me. Were you looking for this, one of them said, handing me my container. It is not full of explosives, is it, they joked. Obviously they had given it a security check. Elderly, breathless and everything, I obviously belonged to the harmless sight-seer category. But how absolutely stupid of me to leave something looking even remotely like a bazooka on top of the Jerusalem walls on Jerusalem Day!

I took it, thanked them, and came down by Damascus Gate — only to find the right-wing youth parade heading straight at me. There were security cordons on all sides, hence nowhere to go except back into the now rather empty suk, the Muslim bazaar, before them. They kept coming at something between a walk and a jog, in blue-and-white ranks three or four abreast, wearing their skull-caps, their kippahs (Hebrew) or yarmulkes (Yiddish), all waving Israeli flags. And neither were they alone, for to their right and left were two covering single files of IDF soldiers, facing outward, their Uzi submachine guns held at the ready. What they were staring at were the Muslim Arab shopkeepers of the entire market, who had all come out — were they required to show themselves, I wondered, so that there should be no suspicious movement inside — and were standing (myself included) side by side, their (our) backs to the wall, arms crossed — was this, too, because the soldiers wanted to see where their hands were, I again wondered — their (our) faces shut tight, unflickering, emotionless. Nobody stirred, nobody spoke. We were just watching the passing marchers. The air was full of unbelievable tension, so thick and dense you could almost cut it with a knife. Strange things can happen to you in such bizarre circumstances. I wasn’t really thinking of the danger, of how I might get out of this in one piece. I started confusing art and reality, past and present. My mind flew to Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966). I was in the casbah, and there were the French paratroopers, leaving Indochina after their defeat at Dien Bien Phu to be redeployed to Algeria, marching up from the harbor area into the city center under Lieutenant Colonel Mathieu, who would train and organize them into torturers.

That afternoon on 7th May 2006, the only sound in the Jerusalem bazaar was the marchers’ spoiled yet nervous chatter. But it was as if nobody heard them. I didn’t. Neither do I have any sense of how it ended. Or how I found the bus station. I only remember the silence. The grim, sorrowing, stony silence.

(*) The Turkish original of this article appeared in Serbestiyet on 13th May. For a previous English version, click https://hist.ihu.edu.tr/en/halil-berktays-diary/.

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.