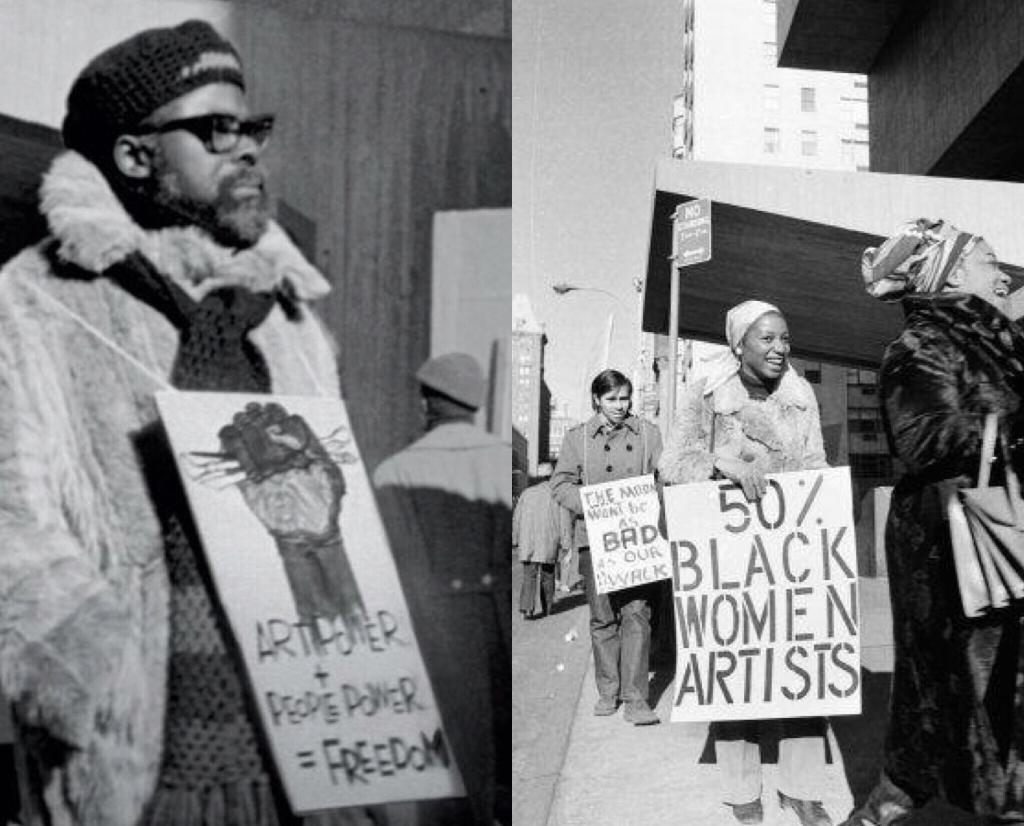

Since the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in May, the momentum for cultural and political change driven by the re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter demonstrations has been extraordinary. Brands and corporations have rushed to acknowledge systemic racism, whether in a genuinely engaged manner or in lukewarm social media posts seeming to address structural inequities. Police reforms have not been embraced all over America. Nevertheless, the Minneapolis City Council unanimously voted to dismantle its police department, and school districts in Oakland, California and Madison, Wisconsin announced plans to terminate their police contracts. Statues that venerate segregationists, slave traders, or Confederate leaders have come crashing down (and not only in the US but also the UK). Beyond such physical symbols of inequality and injustice, there have been serious calls from within British and American academia to de-colonize the curriculum.

The momentum to fight inequality in the workplace continues in the art world. Former and current Brooklyn Museum employees stepped forward in September to denounce the “harm and daily mistreatment” of workers of color by the institution’s executive leadership. The anonymous group “A Better Guggenheim” called for the removal of three top executives (Richard Armstrong, Elizabeth Duggal, and Nancy Spector) in a letter sent to the Guggenheim Museum and published online, detailing allegations of sexism, racism, classism, and abuse. An open letter by three artists who were included in the now canceled Collective Actions exhibition, which I wrote about last month, urged the Whitney Museum to “commit to a year of action — of mobilization and introspection.”

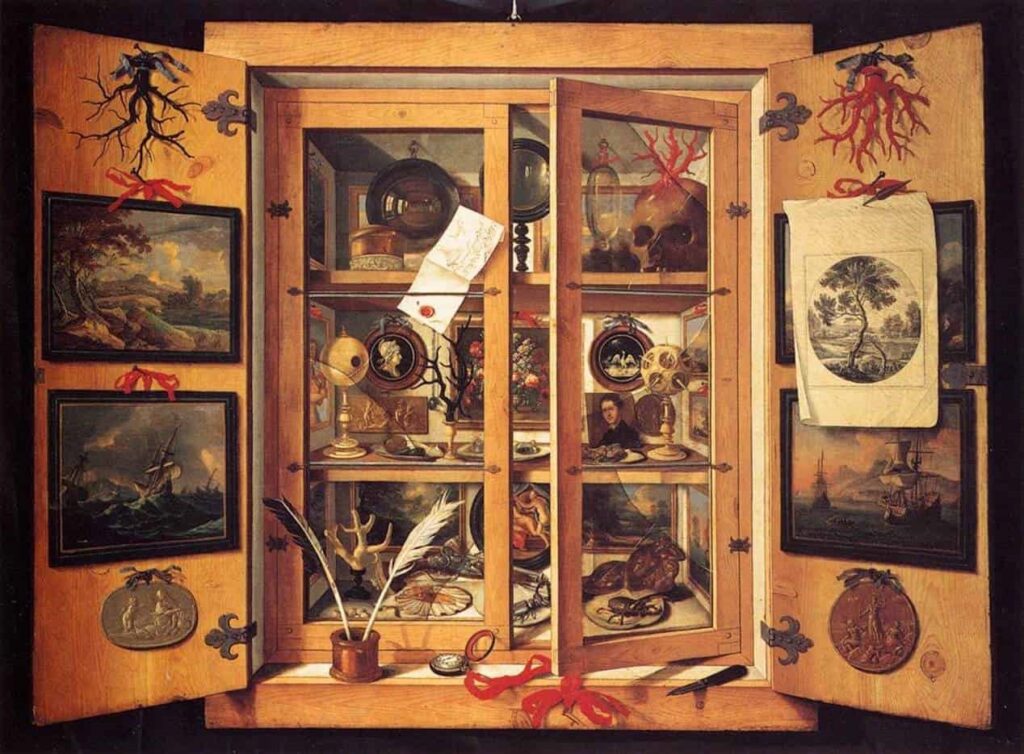

However, there is still a long way to go when it comes to seeing social justice realized in the gallery space. This is true especially of what are known as “universal” or “encyclopedic” museums, as illustrated by a recent installation by the Metropolitan in New York. The museum reopened at limited capacity at the end of August, with its installation “Crossroads,” originally slated to open on March 6, finally accessible to the public. The exhibit claims to “examine the idea of cultural interconnectedness” by telling “thought-provoking stories about shared ideas and artistic forms from around the world, presenting the global history of humankind as a narrative of intersections and change.”

However, as Erin L. Thompson, a professor of art crime at CUNY, pointed out on Twitter, the installation was more “a master class in using your looted antiquities to justify keeping your looted antiquities.” In a short thread, Thompson pointed out examples of looted and stolen items that were displayed, such as a twelfth-century Cambodian bodhisattva figure — which she noted had no feet, a common feature of sculptures “hacked out of Angkor Wat.” The piece (see below) was donated to the museum by a man who purchased it from Douglas A. J. Latchford, a notorious antiquities looter and smuggler who was indicted in New York in 2019 for his crimes. In 2013, the Met had to repatriate two tenth-century Cambodian sculptures, also donated to its collections by none other than Latchford himself. Pointing to other examples of probably looted or illegally exported objects in the exhibit, Thompson concluded that “Yes, the Met can, as the exhibition boasts, present ‘a network of crossroads, among places, eras, and cultures’ — but it does so by keeping art that was taken from these places without their consent. The display text repeats many thoughts from arguments about the value of ‘universal museums’ — the ‘we want one of everything’ model.”

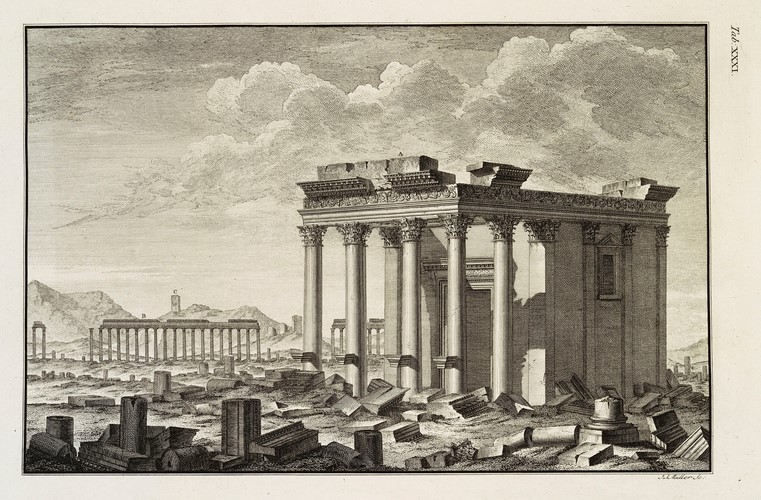

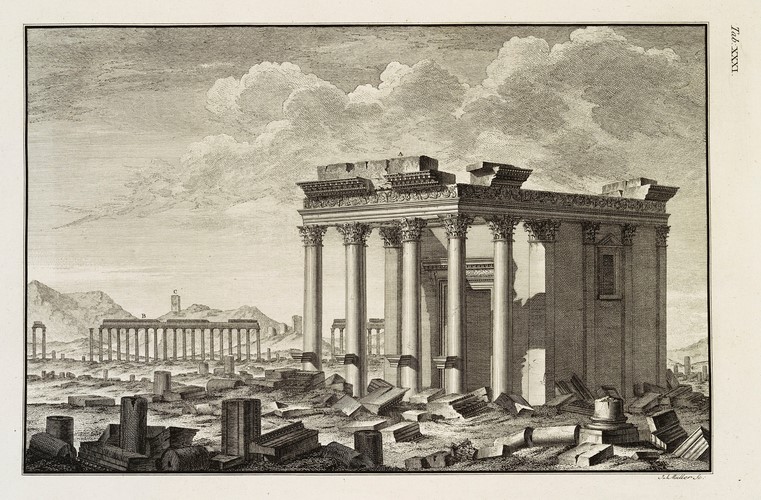

The question of repatriation, that is, of returning art or cultural heritage (often referring to ancient or looted art) to its country of origin or former owners, increasingly became a matter of concern beginning in the latter decades of the twentieth century, particularly due to the issue of Nazi-looted art during the Second World War. Disputed items of cultural property are physical artifacts of a group or society that were taken from another group, usually in an act of looting, whether in the context of imperialism, colonialism, or war. The contested objects vary widely in scope and include sculptures, paintings, monuments, objects of everyday use such as tools or weapons taken for the purpose of anthropological study, and even human remains. The broader issue is what to do with such art, and while repatriation is the most frequently voiced demand, as I will be arguing in the course of this series of articles, it is not necessarily the only solution.

But just stating the problem can be frightening enough. In 2002, eighteen major museums released a “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” which served at least in part as a defense against specific and general allegations of looted objects kept in the collections of such institutions around the world. Of the current signatories, including the Metropolitan, the British Museum, and the Louvre, all except one are located in the West, and over half are in English-speaking countries. The declaration reads: “We should not lose sight of the fact that museums too provide a valid and valuable context for objects that were long ago displaced from their original source. The universal admiration for ancient civilizations would not be so deeply established today were it not for the influence exercised by the artifacts of these cultures, widely available to an international public in major museums.” It concludes by asserting that “museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.”

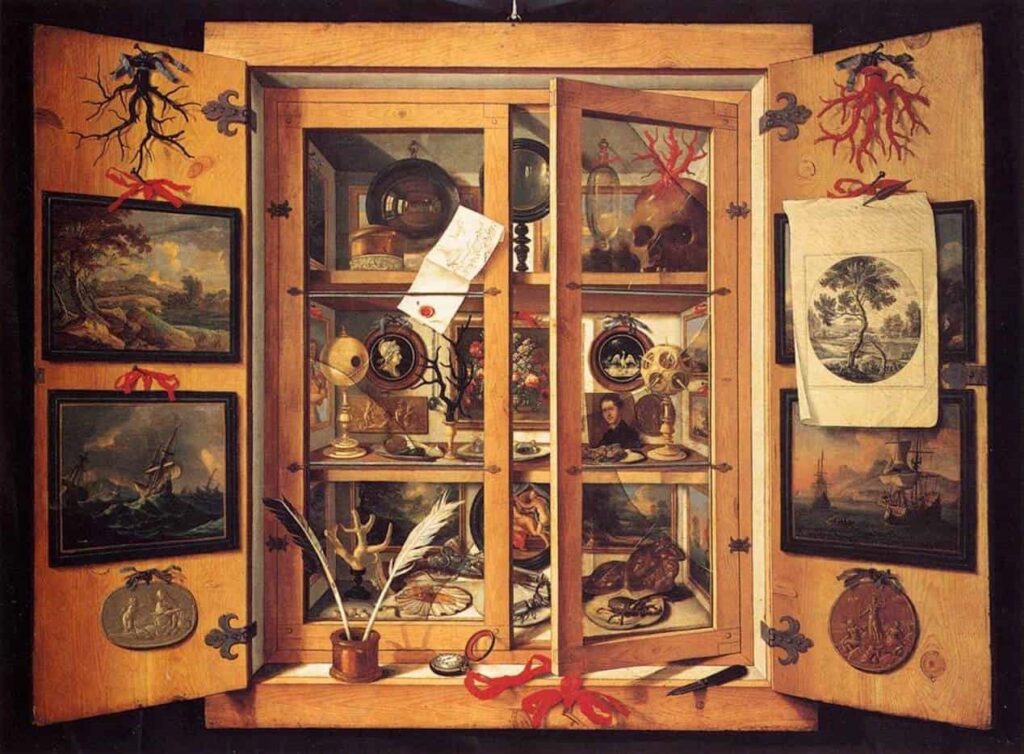

Against this, George Abungu, former director general of the National Museums of Kenya, notes that some museums point to a “universal” culture as “a way of refusing to engage in dialogue around the issue of repatriation.” The reality is that the “universal” museum is not universal at all. The term, which has gradually evolved into the “encyclopedic museum,” implies a neutral, sanitized institution where knowledge floats above all notions of identity and affinity, including class, nation, race, or ethnicity. In fact, museums are deeply political spaces, tied to very specific histories and contexts. In their introduction to Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, Steven Lavine and Ivan Karp make the point that museums draw on the cultural assumptions and resources of their founders-makers in order to weave certain political or social meanings around the objects on display. “Decisions about how cultures are presented reflect deeper judgments of power and authority,” they say, which can “resolve themselves into claims about what a nation is or ought to be as well as how citizens should relate to one another.” What this boils down to is that the “universalism” of a museum is an ideological position that has its own history and politics. It is an unequal, hierarchical “universalism” that is on display. Hence it seems naïve and idealistic, if not absurd, to claim that a “universal” museum exists on an apolitical, non-ideological plane. The objects on display today are inextricably linked to their original contexts as well as the circumstances of their subsequent removal, notwithstanding the “universality” claims of the institution in which they currently reside.

Before diving further into the deeply complicated and nuanced issue of repatriation, I feel it is important to provide a brief overview of such “universal museums” as the Metropolitan or the British Museum.

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.