Just as I expected, it was his own wish to be cremated, and for there to be no religious service of any kind.

So I went, Istanbul to Heathrow, Heathrow to Paddington, Paddington to Chippenham, writing and revising, writing and revising on planes and trains, and on to Semington Crematory south of Melksham. At noon on Friday, 4th November 2016, we stood as six pall-bearers brought his coffin and placed it on the catafalque. His daughter Ayla, my cousin, had written a loving biography and remembrance, which was read out by the celebrant. Two of his former colleagues also spoke, astonishing us all with their account of the scope of his scientific achievement, the extent to which he had stood at the forefront of his profession. Among other things, it turned out that over 1986-88 he had served as the President of the British Institute of Acoustics. All this was something that he never ever mentioned at home. He led a completely compartmentalized life, Ayla had earlier remarked. When she and her husband David went through her dad’s study, they discovered sheets and sheets of paper covered with calculus. Yes, he was a superb mathematician, his colleagues testified (and I immediately thought of his younger brother İlhan, too, as well as their father (my grandfather) Halil Namık Bey, who had been a Mathematics (Riyaziye) student at Istanbul’s School of Engineering (Mühendis Mektebi, later Istanbul Technical University) when he volunteered for the front in 1914 and ended up as an artillery officer at Gallipoli). And beyond his academic accomplishments, the same words and phrases kept occuring again and again. A true democrat. A defender and advocate of equality. Always Labor (how on one formal occasion, he even refused to toast a Conservative politician, quipping that there was no such thing as a decent Tory). Warm, humorous, kind-hearted with everyone, generous with students, quick to put new applicants at ease, protecting women and facilitating their entry into the male-dominated fields of science and engineering — everything, one said, that you could ask for in terms of professorial leadership. Accompanied by the legendary requirement that he introduced for those going abroad for conferences etc — that they must bring back a bottle of the favorite spirits of that country.

When, after Ayla, my turn came, I rather stammered my way, I am afraid, through the following (borrowing in bits and pieces from my previous obituary).

* * *

Especially over his first two decades, Uncle Orhan lived through some harsh times — what Eric Hobsbawm has called an Age of Catastrophe. Born barely half a decade after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, and growing up under Turkey’s own version of a one-party régime, he was even when Hitler came to power, and almost fourteen when, from their Topağacı flat in downtown Istanbul, he and most of the family watched the Nazi diplomats living across the road loudly celebrate the fall of Paris, and his oldest brother, i.e. my father, came and put his hand on Orhan’s shoulder, saying: “Don’t worry, they’ll get what is coming to them.” When that actually happened, in 1947 it was a grimly austere postwar England that he arrived in, and a Birmingham that had had its heart torn out by the Blitz. Still, this became his new, his adopted country, where in the midst of the Fifties’ and Sixties’ Golden Years he settled and made a new life for himself.

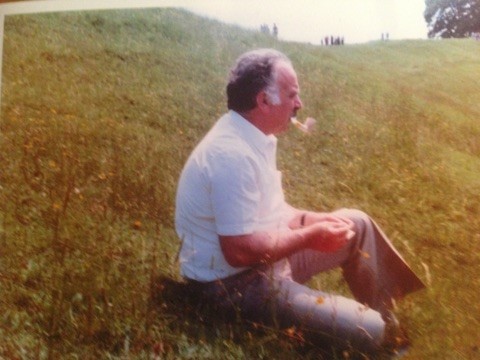

In a family of mostly larger-than-life, heroic-tragic, and sometimes self-dramatizing men, perhaps conditioned into all this by their over-reaction to the world’s tragedies, Uncle Orhan stood out by somehow managing to remain uniquely and eminently sane. He was always fair, modest, honest, and generous, and I don’t think I ever saw or heard him engage in any grand words or gestures, any kind of bombast, pietistics or platitudes. I am unable to say whether this was entirely congenital, or if it was at least also his acquired Englishness, plus the sobriety of his science, his academic calling, that fashioned his understated existence. But one way or the other, I am glad that this is where his ashes will remain. England was always better for him than Turkey’s extremes. — “Our gentle uncle” (in Turkish “yumuşak amcamız”), as my sister Neyyir and I used to call him (implying that there were others who were not so gentle)… Farewell.

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.