[18 December 2019] After “Post-liberalism,” I was also intending to tackle the “foreign meddling and provocation” cliché. But of course, “we” all, meaning China, Russia, Venezuela, Brazil, and Turkey… are being provoked all the time, targeted by this or that dose of “fake news.” So it is not as if that topic is going to grow cold overnight. It can wait a bit. Let’s first dip into recent history — 1915 for example.

In far too many matters, I am afraid, there seems to be a huge difference between where the world is and where we happen to be at the moment. But the worst is that frequently, we differ in not even being aware of this difference.

I have just learned from the internet that tension is escalating between “us” and the United States — basically because the American Senate voted to recognize the Armenian genocide. (In the original Turkish news report, the key g-phrase is in quotation marks by way of implying that this is a false allegation, which of course I cannot go along with; I must also add that as a result of an extremely rare Republican-Democrat agreement, the motion was wholly unanimously adopted.) President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, co-hosted by a joint ATV and A Haber broadcast (two very pro-government channels owned by the same company), appears to have affirmed that such moves are bound to be met with an appropriate response. Thus Turkey, he has said, may equally bring the fate of Americans Redskins [his own words], or the slave trade from Africa, or the massacres perpetrated by the French in Algeria or Rwanda, to the world’s notice. “We do possess these documents,” he has continued; “the archives are full of them.” Hence on this issue Turkey is not going to fall back in defense but is going to go on the offensive, President Erdoğan has insisted: “We are going to prove that the history of the West is a history of racism and colonialism.”

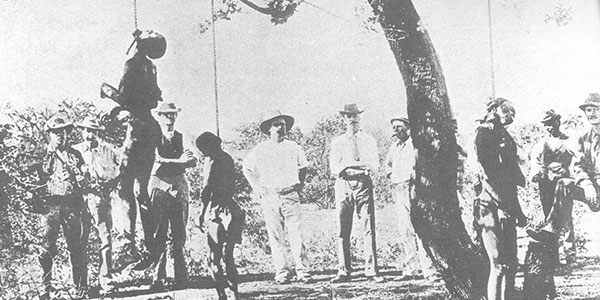

While this last sentence is partially incorrect, it also happens to be partially correct, for yes, the history of the West since around 1500 does involve a significant dimension of racism and colonialism (even though that may not be the whole story). Included in that is, yes again, the dispossession of the native peoples of the America by the whites; plus (let me add) the consequences of Russian expansion into Inner Asia and Caucasia; plus the Atlantic slave trade; plus what the French did in Africa and Indochina; plus (and let me add again) all the violence and oppression inflicted by the British, too, on Africa as well as India. This, indeed, is what I have chosen to highlight up top: after the suppression of the 1896 Shona uprising in former Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, white settlers calmly watching the black Bedreddinian bodies dangling from the trees. Perhaps even more horrible is what you can see below: the price of Belgian rubber extracted from Congo and marketed to the whole world, paid in the form of natives’ hands cut as punishment for disobedience, and forcibly photographed, under the arrogant gaze of their masters, in the hands of yet other natives.

.jpg)

So far, we may seem to be in rough agreement, though there are a few nagging questions at the back of my head. The first has to do with whether extreme violence, conquests, expansionism, torture (including impaling from the rectum up or dangling on giant fish-hooks), invading and occupying other lands and peoples in order to build empires, and then using terror to crush revolts, filling entire wells with severed heads, murdering so many caliphs and grand viziers so as to leave only a very few to die from old age, legitimating fratricide (and practicing it on a massive scale) for the sole purpose of preventing competition for the throne, and even watching your own son being strangled with a bowstring… is limited to the West, or alternatively, may have also been a part of “our civilization.” I am simply noting this possibility and then shelving it for the time being. I hope to come back to it in the near future.

But of course, this may lead into a second question: Is it, therefore, no more than a matter of “what if we committed such horrors, because you did, too”? There is a Turkish saying about two copper kettles quarreling in the kitchen. My, but you do have a black bottom, one says. None blacker than yours, the other retorts. Years ago, Heracles Millas incorporated this into the title of a book criticizing the dreadful symmetries of Greek versus Turkish nationalism. How far can you go with this sort of outlook? Does it mean that everybody, but everybody, should fall silent, and refuse to speak up on behalf of a common humanity?

For the moment, I am going to leave this idea, too, alone, in order to pursue what I consider to be an even more pressing problem. The two pictures above are not taken from any secret source; instead, they (as well as innumerable others like them) may easily be found in English textbooks of history. They carry a no-punches-pulled narrative of the whole multi-faceted reality of the British Empire. They don’t apologise for imperialism and colonialism; rather, they subject it to a comprehensive analysis. And they keep being utilised in all sorts of modern history courses in British or British Commonwealth universities. I have a few hundred of them in my personal library. (I couldn’t refrain from checking; just my British Empire collection runs over five shelves.) More or less the same holds for France, Germany, Italy, Holland, and the United States. Most crucially, these countries no longer subscribe to an official ideology of “national history.” Their governments don’t feel bound by any sharp and strong “ideology of history.” They don’t have any state institutions devoted to manufacturing an “official history” (comparable to the Turkish History Society of a not too distant past, at least in the way it functioned under Ataturkist quasi-military tutelage). Unlike the National Curriculum Board of the Turkish Ministry of National Education, their corresponding curriculum committees do not feel obligated to foist any such “official history” line on primary and secondary education. Neither do they have a uniform set of required textbooks. Instead, their schoolteachers are mostly free to choose their classroom resources. Virtually all archives are open to virtually all research workers — regardless of what their “ulterior motives” might be. So the documents that President Erdoğan speaks of possessing in ominous tones are not really secret but common knowledge. As for the media, they don’t have much to do with character assassination attempts against any scholar who voices not quite so orthodox views. In short, history is free, historians are free, and universities are free. Hence, all those departments of History, Sociology, Anthropology, Archeology etc may design any course they want on the darkest pages of racism, colonialism, ethnic cleansing, massacres or genocides, and incorporate them into their degree programs as they see fit. And if there are objections or contrary views, this mostly takes the form not of a political attack from the outside on scholarship and the academy, but an intra-academic scholarly debate.

As things stand, Turkey’s overall academic environment, and especially the constitutive outside it provides for history, fall far short of such broad, tolerant liberty. But let me bypass even that comparison, and continue to look not inward but outward. Under the circumstances I have outlined, just how is President Erdoğan, and/or our Foreign Ministry, and/or parliament (i.e. the Grand National Assembly of Turkey) going to be able put “American redskins, the African slave trade, Algeria and Rwanda” in the world’s eye? Are such statements likely to shake things up, and cause something of an intellectual earthquake? Are these or other facts going to come as such a shocking surprise that the West will promptly succumb to an unprecedented guilt complex? But who doesn’t know all this anyway? Or alternatively, is Mr Erdoğan going to be confronted by any government who may want to deny part or all of this? It is of course a possibility, though it is likely to be limited to Trump, Putin and their ilk, that is to say our protectors of the moment that we seem to be pinning our hopes on. Apart from them, might even the swashbuckling Boris Johnson and his impending Tory cabinet be inclined to deny how the Great Indian Mutiny was actually suppressed in 1857? I simply don’t think so.

But so, the question is not whether we have all been guilty of such horrors in our human past. Rather, the question is whether we might today be allowed to deny them for the sake of this cause or that raison d’état. It is also a question of whether scholarship and scholarly institutions are genuinely free from such external requirements. This is our tiny difference.

Yazıyı beğendiysen, patronumuz olur musun?

Evet, çok ciddi bir teklif bu. Patronumuz yok. Sahibimiz kar amacı gütmeyen bir dernek. Bizi okuyorsan, memnunsan ve devam etmesini istiyorsan, artık boş olan patron koltuğuna geçmen lazım.

Serbestiyet; Türkiye'nin gri alanı. Siyah ve beyazlar içinde bu gri alanı korumalıyız. Herkese bir gün gri alanlar lazım olur.