Halil Berktay

The Turkish original of this article was published as Kipling ve aklını kaçırmamak on 17th January 2016.

“If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs and blaming it on you…”

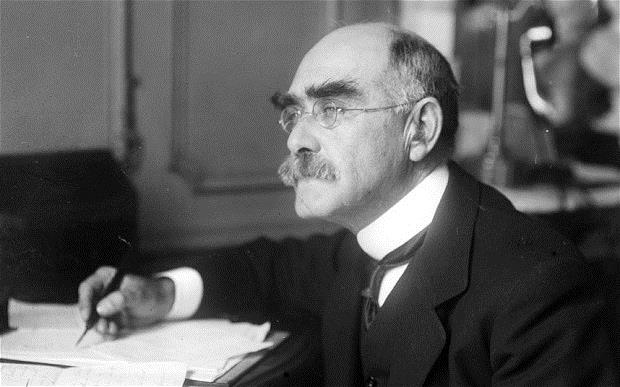

The first two lines of Rudyard Kipling’s famous “If–” of 1895. I have been repeating them to myself for the last few days. No, not the bit about anybody blaming anything on me; that’s not the point. I am walking around at home muttering only the “ … when all about you / Are losing theirs” part.

Let us not get lost in narrow ideological criteria. So what if Kipling’s politics were not very trustworthy? And they were not. W. H. Auden is another great poet, and one for whom feel genuine affection. A third great poet whom I also like very much is W. B. Yeats. There is something, a textual fragment, that draws them together. When Yeats died, Auden wrote his “In Memoriam.” In three quatrains of the third section that he would later delete, but which are nevertheless included in all published versions, he dwelt on the complex relation between literature and politics, and what Time renders permanent, why, and in spite of what: “Time that is intolerant / Of the brave and the innocent, / And indifferent in a week / To a beautiful physique, / Worships language and forgives / Everyone by whom it lives; / Pardons cowardice, conceit, / Lays its honours at their feet.” He went on to become even more specific: “Time that with this strange excuse / Pardoned Kipling and his views, / And will pardon Paul Claudel, / Pardons him for writing well.”

With his still leftist public voice of 1939, Auden was clearly denouncing, or rather pretending to denounce, Claudel because of his Catholicism, and Kipling for his imperialism. Hardly anybody else, indeed, has come to be mentally, emotionally and ethically as identified with the British Empire and its colonial mission as much as Kipling. On the one hand there is a new phenomenon of “youth,” and on the other Kipling’s own complicated relationship with India. Capitalist development over the second half of the 19th century (during what Eric Hobsbawm has called, in the title of the second volume of his classic trilogy, The Age of Capital) gave rise to an initial affluence as well as universal education, which in turn fostered the emergence of a new “youth” age-group between ‘”childhood” and “adulthood.” Unlike what had been previously the case in traditional society, “childhood” no longer gave way directly to “adulthood.” Instead, at least for the middle classes, a new socio-cultural window of “years of adolescence and youth” was being opened.

In turn, this led to the question of how to harness and where to channel this new youth’s energies. In an era of rising nationalisms, this meant putting them in the service of the nation-state. “Swedish gymnastics,” for example, emphasizing mass uniformity and coordination, were invented at this time (and brought to Turkey by Selim Sırrı Tarcan). It was also in the same era that special youth and sports festivities were invented (and once more, imported first to the Ottoman Empire in its last decades, to be transferred from there to the Turkish Republic). Paramilitary youth organizations began to be founded. For Great Britain, this implied the forging of an imperial-nationalist youth that would be well-prepared to stand guard at the frontiers of Empire and fight its distant battles, that would therefore be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills as well as the requisite determination, daring and boldness. In a way, the enthusiasm and theory for this project may be said to have been provided by Kipling through literature, while it was an army man, General Baden-Powell, who came up with the practical and organizational know-how. In The Jungle Book (1984), Kipling idealized Mowgli as a (native) man-child type who comes to master the forest and its secrets as well as the animals that he lives with so as to lead and dominate them through his superior intellect. Then in his novel Kim (1901), he further idealized a young white (English-Irish) intelligence agent who went so successfully native as to become indistinguishable from the Indians. All this served as an ideological foundation for Baden-Powell to set up his first Scouts Organization in 1907. It was followed not only by other states and governments, but also by a proliferation of the youth sections and paramilitary youth organizations of various political parties. This was a way of inserting youth-based violence into militant politics. Over time, there emerged the Black Shirts (squadristi), of Italian Fascism, the Brown Shirts (SA’s) and later the Hitler-Jugend (Hitler Youth) of German Nazism, the Soviet Communist Party’s Komsomol and all other communist youth organizations that it inspired, or Mao’s Red Guards during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. (In Turkey in the heyday of the One Party dictatorship, a notable extension of this trend was the militarization of education, the introduction of compulsory military training into higher education, and the incorporation of Istanbul University students into “training regiments.”)

To go back to Kipling; this is also the context for the “If–” poem of 1895 (i.e. a year after The Jungle Book and Mowgli). Its starting point seems to be advice for his son John, whom he would proudly send to his Western Front death in World War I (see the tv series My Boy Jack of 2007). But it can also be taken, more generally, as a inaugural lecture for an as yet unfounded Scouts Organization. He goes down the whole list of the Stoical values and code of behavior of the Victorian era: Coolness, patience, truthfulness, self-possession, understatement, no vindictiveness, no boasting, no display of arrogance, no showing of. To dream but not to drift into illusions; to think but not to become lost in ideas; to take risks but not to bat an eye in case of loss; not to be devastated by disaster nor dizzy with success. Resilience come what may. Neither fear of the enemy nor excessive devotion to friends. To evade all extremes, to maintain a sense of balance, not to show one’s feelings. Think of Atatürk’s “Address to Turkish Youth” (1927) that is on the opening pages of every primary-middle-high school textbook, that is displayed in the entrance hall of every school, or on the walls of every classroom. In a way, this, too, is like Kipling’s address to the British youth of his time. But there is a difference. Kipling’s text is not based on specific circumstances; it is not concrete or directly political, but much more general, abstract, and ethical. It is not about what policies or political actions to adopt when country and nation are in danger, but an entire attitude and force of character needed to face life. Precisely for that reason, it is able to achieve the status of a significant example of the relative autonomy of ideology (and art). Any great work of art or literature, whatever its starting point might be, is able to attain greatness to the extent that it can capture a general and universal moment of humanity. Kipling’s promise of becoming “a Man,” too, is not limited to Britain and imperialism, but extends to a wider universality, to an overall human potential. He puts before us, wherever he might be (and of course it is a he, so no need here for gender-correctness) a certain type of a humble, resilient, self-sufficient, non-ostentatious, in brief a solid and steady modern hero. Like Tennyson’s Ulysses (Odysseus), he issues a positive, affirmative call to strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.

I cannot, of course, say that I like all its lines and phrases, everything in it. On the contrary; there is a lot in it that I find much too pompous, pretentious, didactic or bombastic. Still, there are other verses that touch me in their simplicity: “If you can wait and not be tired by waiting” or “being lied about, don’t deal[ing] in lies.” And surely this: “If you can bear the truth you’ve spoken / Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools, / Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken / And stoop and build’em up with worn-out tools.” I for my part gave at least half of my life to Marxism and the Left. And it, too, has been “ broken,” comprehensively shattered. Yet here I am, stooping to rebuilding everything with my worn-out tools in order to keep on living and thinking.

Clearly, these are character traits (embodied in individuals) that are also close to my own heart. He or they may have pursued imperial aims of conquest and colonization in the past. Today he might be expected to commit the same strengths to other struggles. I would, for example, be so very happy if some contemporary Turks, intellectuals and politicians alike, were to acquire just a little of these qualities of patience, moderation, and a calm and quiet sort of resilience.

But alas! On the one hand we have this public statement, signed by 1128 academics, that is true to everything but the truth, which is a mind-boggling travesty of all the facts at our disposal. On the other hand, we have been facing a wave of legal accusations, detentions, investigations and lay-offs initiated by explicit and repetitive calls to that effect by government leaders and statesmen — who should have known better than to confuse political struggle with judicial and other forms of chastisement. For the first, where is fairness, where is any respect for truth? And for the second, where is moderation, patience, calmness, sense of balance? If I had any faith, I would be praying, begging God to protect my sanity. It is much too late; at this age I cannot very well take refuge in religion. Instead I have only my own identity and personality, my inner resilience, my capacity “to be a Man.” That is why I have to make do with Kipling’s verses, inviting sleep at night by murmuring into the dark: “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same.”

Bu yüzden, evin içinde “herkes aklını kaçırırken, bari sen akıl sağlığını koruyabilirsen” diye mırıldanarak dolaşıyorum.

That is why I keep walking around at home muttering something about keeping my head when all about me, others are losing theirs.