[24.4.2019] Yesterday was April 23 (1920); today is April 24 (1915). Another anniversary, though of a different kind.

I am neither pro-Turkish nor pro-Armenian, nor for that matter pro-anything. Class, nation or ideology — I have no team that I root for in history. I did once, but no more. And it’s been a long time since. So during the furore over May 1, 1977, for example, I could only laugh at those “utilitarian” would-be historians whose dismayed response to my disclosures was that “now was not the right time to say all this.” There is no such thing as the right time to say the truth. As for myself, for quite some time I have been a historian who abides by nothing but the truth. My profession’s requirements, I have made into my own personal ethics. I can be mistaken, but I cannot wilfully lie or distort anything. Fuat Köprülü said it all, and most eloquently, too, 73 years ago: “… as I keep searching for historical reality, I can never allow myself to forget that it is scholarly truth that I serve above all… And indeed, historical truth can never be to the detriment of the Turkish nation’s real interest.” (From his introductory notes to the 1946 Turkish edition of W. Barthold’s History of Islamic Civilization, reprinted in 1962.)

During the final decline and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, various mutually hostile nationalisms entered into cutthroat competition with each other. All sought to establish their own territorialities violently expunged of “others.” Starting in the 19th century, first Rumelia, then Crete (which my own family fled from), then the Pontus region of the eastern Black Sea, and eventually East Anatolia were engulfed in local, small-scale, low-density ethnic warfare. All sides organized their own bands and tried to terrorize the rest. Raiding each other’s villages, burning their crops, setting fire to barns and cottages, killing the men and raping the women… In those dark Times Of Troubles this is what “we all” did to each other. Do you have killers of this sort in your families? I do. I have not minced and I am not going to mince my words about it (a Rumelian immigrant would call it speaking dobra dobra). I can’t really know if others are hiding any ghosts in their cellars or basements. They may or they may not. Such things are hardly ever mentioned in public. Yet another problem is that somebody else’s hero might be a monster to us, or our heroes might be their monsters. What a mess. And who threw the first stone? “They did,” naturally, while “we only defended ourselves.” Of course there is a catch: everybody says the same. Conversation becomes terribly difficult, and nearly impossible to confront the past.

When the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 ended in catastrophic defeat, Macedonia was first surrendered to Bulgaria at San Stefano, but then returned to the Ottoman Empire through the Berlin Treaty of the same year. Hence it promptly became a quadruple killing field, oozing blood and pus from every cell, between rival Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek guerrillas as well as Ottoman gendarmes on “anti-brigandage” missions. A step further, it triggered the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. Especially Bulgarian nationalism, through its monarchical nation-state and army, inflicted untold horrors on its newly conquered Muslim Turks, authorizing terrible massacres.

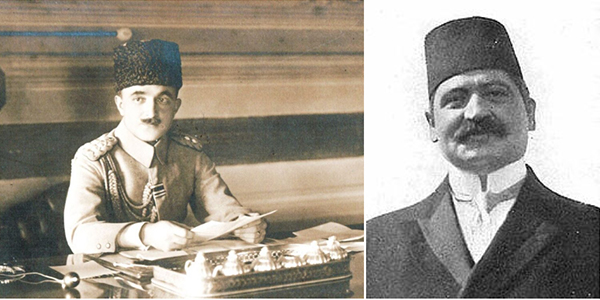

In 1908, the Unionists had proclaimed Liberty for all. The Balkan defeat had the further effect of accelerating their shift from Ottomanism (or a policy of “uniting all ethnic groups”) to outright Turkism. In the eyes of these new, ambitious yet fearful Türkish nationalists, all such non-Muslims as were left behind in 1913 became wholly suspect. Together with his Special Organisation hit-men, Enver had staged a coup within a coup with his 1913 Bâbıâlî Raid, after which he, Talât Paşa and Cemal Paşa began to rule as virtually a military dictatorship with the support of the CUP’s parliamentary majority. “If not today, then tomorrow, they too will rise and stab us in the back.” This is basically how the Triumvirate came to regard Armenian nationalist activity in the eastern provinces as well as the complaints or demands of their Istanbuliote intelligentsia. Inevitably, the Great Powers, and especially Tsarist Russia, also had their fingers in the pie. The pressure they exerted for reforms in heavily Armenian-populated provinces was taken as proof that such interventionism must gradually escalate, so that after Crete, Western Armenia, too, would take the road from autonomy through independence to annexation (this time by Russia).

By 1914, therefore, a bitter Unionist vindictiveness had emerged, probably still without a concrete plan but evincing, in Ron Suny’s words, a clearcut “affective disposition.” It was also a very scientistic generation, inclined to believe in anything advertised in the name of science — and hence also in all the latest pseudo-science. Ömer Seyfettin’s Balkan stories set in social time, and especially Primo and A Pure White Tulip, reflect the extent to which this one-and-a-half generation of Turkish nationalism had turned to Social Darwinism, loudly (and harshly) proclaiming that “might is right” where “only the fittest can survive.” And meanwhile, virtually all Rumelia had been lost, leaving nothing but a poor, backward, squalid Asia Minor to fall back on. So if Istanbul, too, were to fall (as had almost happened in 1878 and 1912), they would have no option other than to put up a last-ditch resistance in Anatolia (as aventually happened over 1919-22). But back in 1914, even that Anatolia was not really safe — because of its sizable Greek and Armenian populations.

So in this sense, World War I played into the three warlords’ hands. As hostile Entente powers, neither Great Britain and France nor Russia could intervene any more, which meant that Armenian nationalist parties and intellectuals were suddenly isolated and deprived of all possible protection from the outside. It was in this setting that the ultimate decision was taken to go in for pre-emptive action. All the pent-up fury of that anxious, uneasy and resentful Unionist nationalism came crashing down on the heads of Ottoman Armenians.

This, now, was no longer a local, horizontal and low-density kind of grassroots-level ethnic warfare. Instead, it was vertical state action from the top down. Just what did they do, or how did they do it? This is not the place for detailed operational descriptions or analyses. I have written enough about that in the past (as have many others, so that a once-solid wall of silence and denial has been torn to shreds). I am just going to cite a single source, albeit one of irrefutable import and significance. It also happens to be a solidly native and national witness: Halil Menteşe, who was so much of a dyed-in-the wool Unionist as to be entrusted with the presidency of the Ottoman House of Representatives, positioning him as an ever-reliable fourth man among the CUP’s political cadres. The following lines are from his memoirs (ed. İsmail Arar, Osmanlı Mebusan Meclisi Reisi Halil Menteşe’nin Anıları [Hürriyet Vakfı Yayınları, 1986], pp 215-216). When war was declared, Halil Bey was in Germany. Repeatedly told by Talât Pasha to extend his stay, he was allowed to return after two months:

“When the train stopped at Ayastefanos [Yeşilköy], the late Talât, who had been waiting there, made his way into my carriage. ‘Tell me, my dear Halil,’ he said; ‘what did you have to say in Berlin about this Armenian deportation affair?’ When I related my conversations with German leaders on this topic, he laughed and patted me on the knee: ‘Dear Halil, I have done you grave injustice. If Halil were here he would inflect my determination, so let him return after I am done with this business, I decided, though it seems that I was mistaken.’

“One day in Istanbul I dropped in on him in his Yerebatan residence. I found Talât by the phone. He did not seem to be his normal self. His face was dark, his eyes bloodshot. ‘But my dear Talât, what’s the matter?’ I inquired: ‘You seem to be in quite an abnormal state.’ ‘Better not ask,’ he replied. ‘I received various telegrams about the Armenians from [Erzurum governor] Tahsin, which so upset me that I couldn’t sleep all night. It is not anything that a man’s heart can really take, but if I hadn’t done it to them they would have done it to mine. And indeed, they had already begun to do so. It’s a fight for national survival.’”

I have put a few key phrases in bold letters. It is perhaps time to pose some questions for textual analysis, at nothing fancier than the undergraduate or even high school level. (1) In what way was Talât Pasha worried that Halil Bey might have “inflected” or had an impact on his, Talât Pasha’s “determination” (or morale)? Why did Talât want to hurry and “be done” with “this business” before Halil’s return from Germany?

(2) Otherwise “they would have done it to mine,” he says. Does this fit in or not with my previous reference to “pre-emptive action”? (3) “If I hadn’t done it to them,” he also says. Just what do you think Talât Paşa may have done (or ordered to be done) to the Armenians that “a man’s heart cannot take”? (4) Do you see any connection between Social Darwinism and Talât’s turn of phrase about “a fight for national survival”? (5) Does this same expression about “a fight for national struggle” shed any light on (a) why (to what end) some things may have been “done” to the Armenians in 1915; and (b) what might have been the likely outcome, or at least what was intended as the likely outcome?

We do know the outcome, of course, but let me say it one more time, at least just that part. Talât Paşa achieved what he wanted. The Ottoman Armenians’ “national existence” came to an end. In early 1915 the Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire numbered around 1.5 million. They basically vanished, to the point where only a few thousands have survived. Call it what you want. Massacres. Ethnic cleansing. Extermination. Annihilation. Mass murder. Medz Yeghern. Genocide. Völkermord.

What’s in a name? In terms of our real, concrete historical understanding, does it really matter?

———————————————–

(*) This is a free translation, with a few additions, of the Turkish original that was published two days ago in the Serbestiyet web site; see Adına ne derseniz deyin, 24th April 2019.